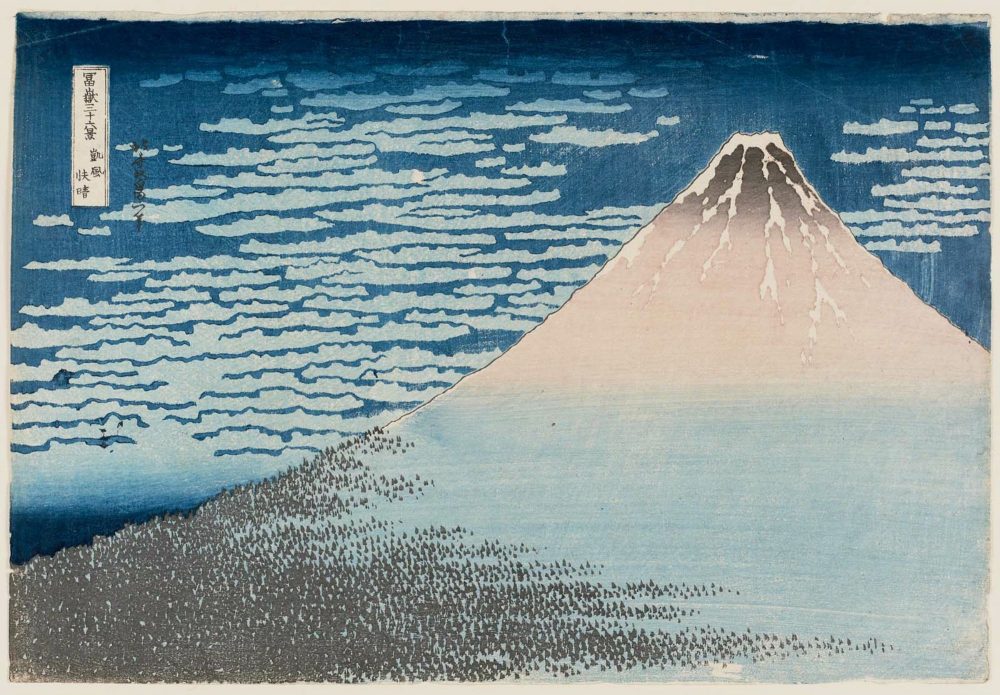

If you enjoy Japanese woodblock prints, that appreciation puts you in good company: with Vincent van Gogh, for example, and perhaps even more flatteringly, with many of your fellow readers of Open Culture. So avid is the interest in ukiyo‑e, the traditional Japanese “pictures of the floating world,” that you might even have missed one of the large, free online collections we’ve featured over the years. Take, for instance, the one made available by the Van Gogh Museum itself, which features the work of such well-known masters as Katsushika Hokusai, artist of The Great Wave off Kanazawa, and Utagawa Hiroshige, he of the One Hundred Views of Edo.

Edo was the name of Tokyo until 1868, a decade after Hiroshige’s death — an event that itself marked the end of an aesthetically fruitful era for ukiyo‑e. But the history of the form itself stretches back to the 17th century, as reflected by the United States Library of Congress’ online collection “Fine Prints: Japanese, pre-1915.”

There you’ll find plenty of Hokusai and Hiroshige, but also others who took the art form in their own directions like Utagawa Yoshifuji, whose prints include depictions of not just his countrymen but visiting Westerners as well. (The results are somewhat more realistic than the ukiyo‑e London imagined in 1866 by Utagawa Yoshitora, another member of the same artistic lineage.)

As if all this wasn’t enough, you can also find more than 220,000 Japanese woodblock prints at Ukiyo‑e.org. Quite possibly the most expansive such archive yet created, it includes works from Hiroshige and Hokusai’s 19th-century “golden age of printmaking” as well as from the development of the art form early in the century before. Even after its best-known practitioners were gone, ukiyo‑e continued to evolve: through Japan’s modernizing Meiji period in the late 19th and early 20th century, through various aesthetic movements in the years up to the Second World War, and even on to our own time, which has seen the emergence even of prolific non-Japanese printmakers.

Of course, these ukiyo‑e prints weren’t originally created to be viewed on the internet; the works of Hokusai and Hiroshige may look good on a tablet, but not by their design. Still, they did often have the individual consumer in mind: these are artists “known today for their woodblock prints, but who also excelled at illustrations for deluxe poetry anthologies and popular literature,” writes the Metropolitan Museum of Art curator John Carpenter. His words greet the visitor to the Met’s online collection of more than 650 illustrated Japanese books, which presents ukiyo‑e as it would actually have been seen by most people when the form first exploded in popularity — not that, even then, its enthusiasts could imagine how many appreciators it would one day have around the world.

Below you can find a list of prior posts featuring archives of Japanese woodblock prints. Please feel free to explore them at your leisure.

Related content:

Download Hundreds of 19th-Century Japanese Woodblock Prints by Masters of the Tradition

Download 2,500 Beautiful Woodblock Prints and Drawings by Japanese Masters (1600–1915)

Enter a Digital Archive of 213,000+ Beautiful Japanese Woodblock Prints

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities and culture. His projects include the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.

Thank you